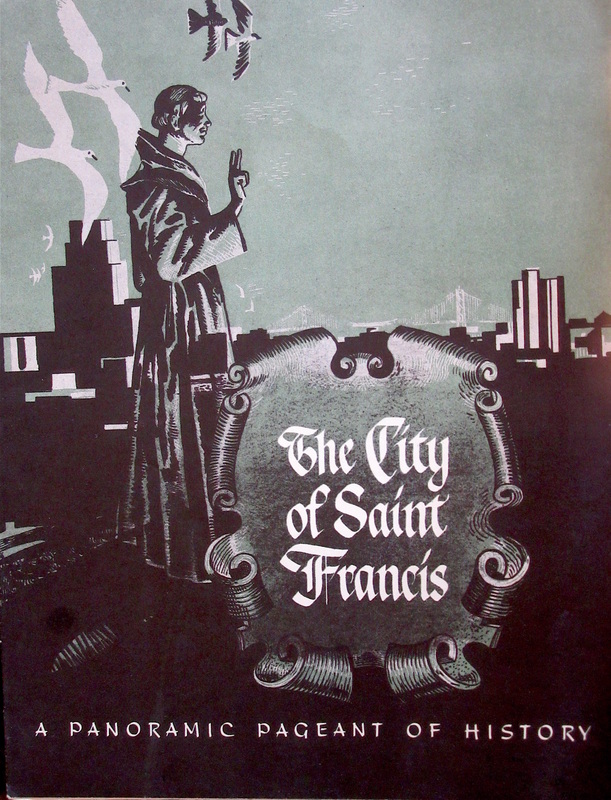

San Francisco murals - 1954

A Study in Murals

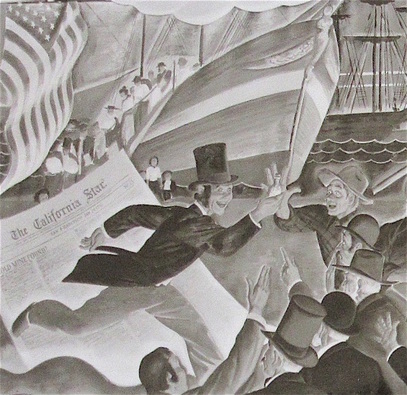

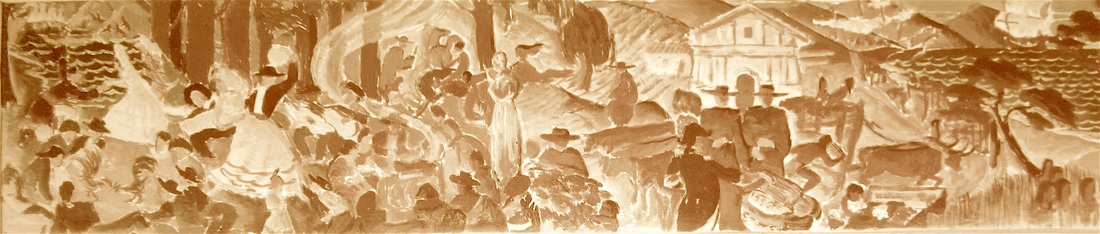

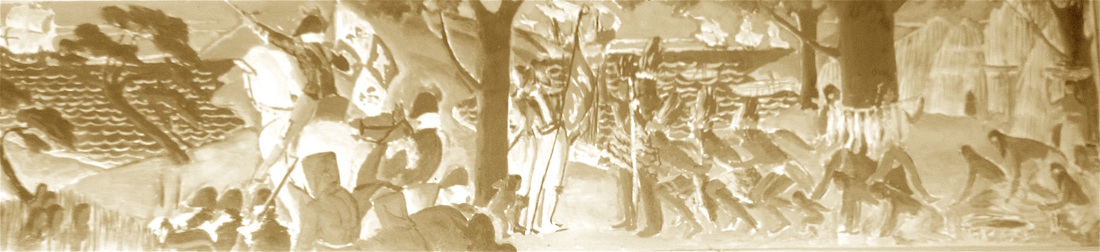

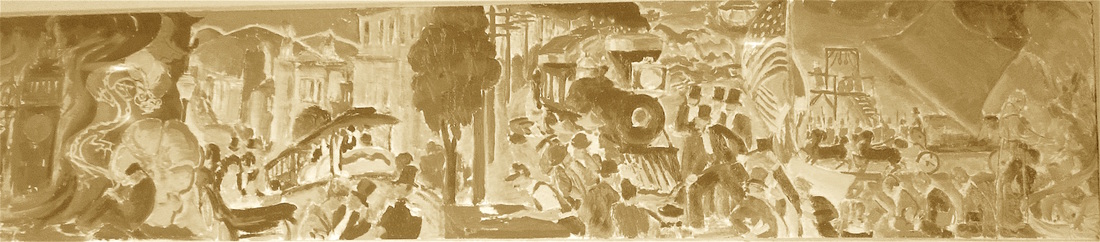

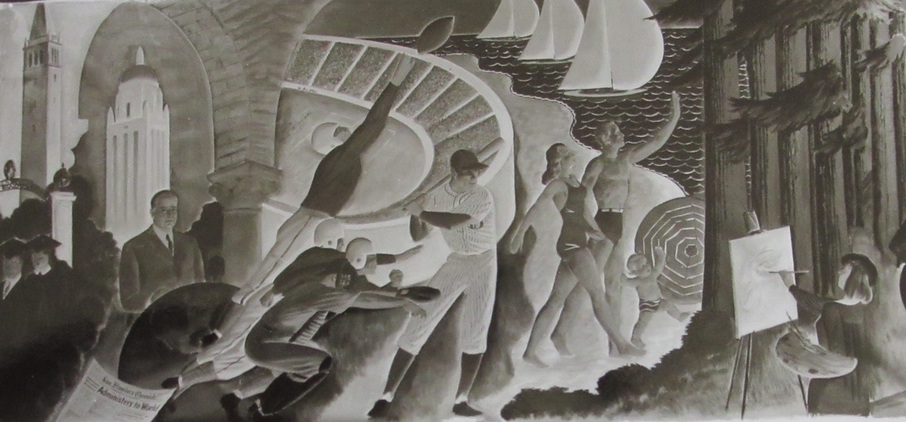

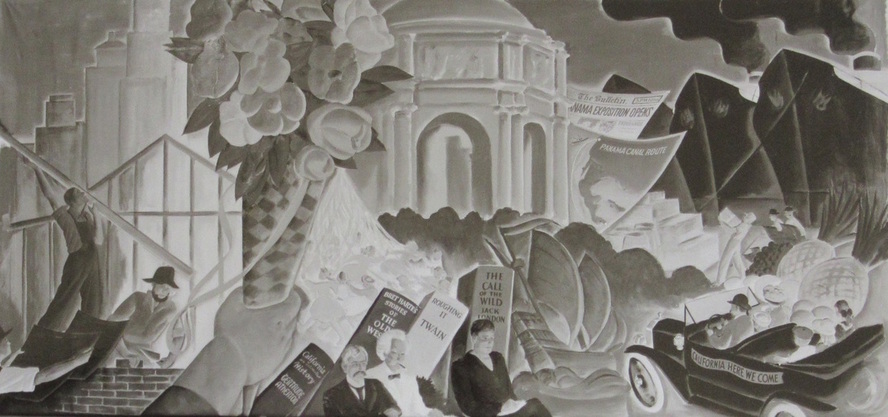

The less detailed slides below show the San Francisco murals' original illustrations that were used for the final versions that appear in black and white slides shown below the work up illustrations. Detail is added to the final version as shown on the below two images.

Photos of the murals

1 2

3 4 5

6 7 8

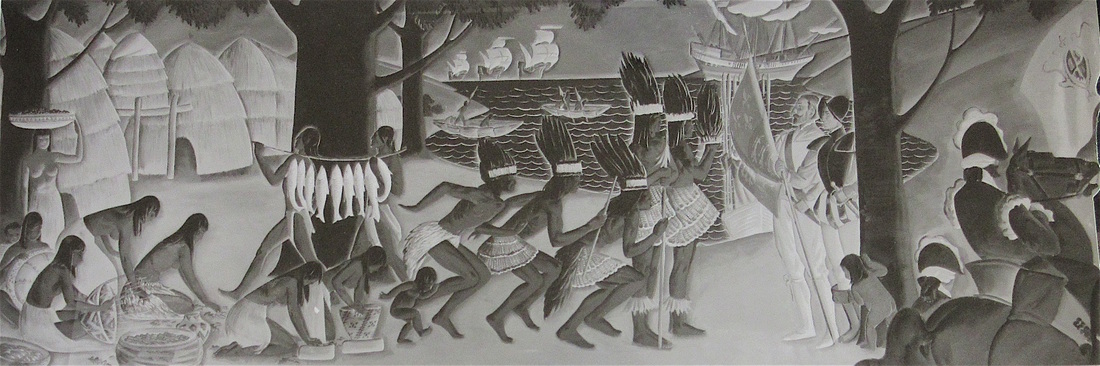

Primitives, Pirates and Padres

More than four centuries have passed since Jaun Rodriguez Cabrillo dropped anchor in the Gulf of the Farallones . . . the first European to visit the San Francisco region. Buffeted by tides and wind, he soon set sail, not knowing that he was within a few miles of the safest anchorage on earth. For untold years before the coming of Cabrillo . . . and for two-and-a-half centuries after he planted the flag of Spain in this virgin land . . the primitive Indians of the Bay Region carried on their peaceful, pastoral lives. [1] In every sense they lived off the country. Reeds, called tules by the Spaniards, made their rude huts and fragile but buoyant rafts. From the oak trees came the acorns that were their staple diet. From the sea came fish, mussels and the tasty little California shrimp.

They had no weapons, because they made no war and confined their hunting too such small game as could be caught in the hands. Primitive . . yes, but happy and unafraid. They greeted the white men with ritual dances and gifts of their one claim to culture; remarkably fine baskets of grass woven so tightly as to be water tight.

In 1597 came Sir Francis Drake, that gentleman adventurer who combined legalized piracy with service to the Queen. [2] He, too, missed the narrow entrance to the bay and landed to the north, at the shallow bay that bears his name. Following the custom of the time, he unfurled the Royal Standard and claimed "New Albion" for England. Two other great navigators, Cermeno and Vizcaino missed the harbor, which was finally discovered by a top sergeant on horseback.

That sergeant was Jose Francisco Ortega, and his discovery . . . like so many great discoveries . . . was an accident. [3] In 1769 Don Gaspar de Portola set out from Mexico seeking the Bay of Monterey, but passed it by. He realized this fact when he sighted the outline of Punta de los Reyes (Point Reyes) and decided to send a party on to view the anchorage of Drake, Cermeno, Cabrillo and Vizcaino . . . which had been titled "Pueto de San Francisco".

That party, under Ortega, failed . . . because they found their way blocked by what is now called the Golden Gate. From a hill on the peninsula, Ortega and his party looked across miles of land-locked harbor. The date was November 2, 1769.

Further overland exploration of the Bay area followed, and in 1775 Don Juan Manuel de Ayala, captain of the ship San Carlos, [4] braved the unknown dangers of the Golden Gate and dropped anchor off what is now Sausalito at ten-thirty on the evening of August fifth . . . the first of tens of thousands of ships to find shelter in the Bay.

The discovery of this mighty harbor had been received with great excitement in Spain and Mexico City, and His Excellency Señor Frey Don Antonio Maria Bucareli y Ursua, Viceroy, Governor and Captain-General of New Spain, ordered the Captain of the Presidio of Tubac, in what is now Arizona, to make up a party and colonize the shores of the Bay. The good Captain, Don Juan Bautista de Anza, set forth with thirty married soldiers, their families and selected civilians.

In that party were men who's names have a familiar ring to San Franciscans and Californians; Alviso, Peralta, Sanchez, Castro, Benal, Valencia.

Don Jan fell ill at Monterey, and the party went on under Don Joseph Joachim Moraga. After a march of ten days, the settlers reached the shores of a lagoon that had been named for Nuestro Senora de los Dolores. Here the two priests of the party, Frs. Palou and Cambon, built a rude chapel, and in it was a celebrated first mass . . .on June 29, 1776, just a few days before the great event took place in far-away Philadelphia which was to have a profound effect upon the future of this just-born Spanish settlement on San Francisco Bay. On July 18 the San Carlos came in with supplies, and the military Presidio was established.

In October the Mission was completed, [5] and Fr. Palou wrote in his diary: "I sang Mass with the ministers, and at its conclusion a procession was formed . . . The Function was celebrated with repeated salvos of muskets, rifles and the swivel guns that were brought from the bark for this purpose, and also with rockets . . In the afternoon the men returned to the presidio and the crew went on board, the day having been a joyous one for all. The only ones who did not enjoy this happy day were the heathen". The Heathen . . who had learned about guns and white men by now . . needed the special protection of St. Francis. [6]

The Spaniards who had come as soldiers were granted vast Ranchos by the King, but agriculture was primitive and little was raised except half-wild cattle. Only the Padres planted vineyards and olive groves and fig trees. The rancheros were too busy with fandangos, cockfights and barbecues. [7] All supplies came from Mexico City, and foreign ships were forbidden to trade with California.

But by 1800 the Gulf of the Farallones was crowded with Yankee and Russian ships of the Russian-American Company, hunting sea otter and seals. Inevitably these ships and the whalers who wintered in the Bay, traded illegally with the Californians.

Charles Caldwell Drake, in his fascinating book "San Francisco A Pageant" says "The list of articles in the New England ship which visited the coast in 1813 and was seized for smuggling reads like a Sears, Roebuck catalogue."

Russian interest in the San Francisco area was intensified when Nicolai Petrovich Rezanov sailed into the Bay in 1806, seeking food for the starving Russian colony at Sitka, Alaska. He bargained with Don Jose Arguello, Commandant of the Presidio . . . and fell in love with sixteen year old Dona Conception Arguello. He got his food,but his suit for the hand of "Concha" was complicated by his Greek Orthodox religion.

Rezanov sailed for Alaska with the promise to return . . after he had crossed Siberia, persuaded the Czar to negotiate a trade agreement between Russia and California, and had visited Rome to persuade the Pope to sanction the marriage. No more was heard of Resinov, and Dora Concepcion helped the Franciscans minister to the poor and sick, there being no convents in California. Thirty-six years later she learned that her lover had died . . still true to her . . while crossing Siberia.

As the nineteenth century advanced, the little colony grew . . but not much. A few adventuresome Yankees settled in Yerba Buena (Good Herb), and trade restrictions were gradually relaxed or overlooked.

Then in 1821, the Spanish-American colonials revolted, Mexico became an independent nation . . and California was part of Mexico. Few persons realize that the Spanish flag flew over Yerba Buena and the Mission San Francisco de Asis for only forty-five years. Under Mexican domination the padres lost their power, and eventually the missions were secularized. An era was coming to an end on the West Coast of America. To the East, across the Serra and the Rockies, a ground swell was rising that would soon crash on the shores of San Francisco Bay.

[from the original Sears introduction pamphlet - 1940]

They had no weapons, because they made no war and confined their hunting too such small game as could be caught in the hands. Primitive . . yes, but happy and unafraid. They greeted the white men with ritual dances and gifts of their one claim to culture; remarkably fine baskets of grass woven so tightly as to be water tight.

In 1597 came Sir Francis Drake, that gentleman adventurer who combined legalized piracy with service to the Queen. [2] He, too, missed the narrow entrance to the bay and landed to the north, at the shallow bay that bears his name. Following the custom of the time, he unfurled the Royal Standard and claimed "New Albion" for England. Two other great navigators, Cermeno and Vizcaino missed the harbor, which was finally discovered by a top sergeant on horseback.

That sergeant was Jose Francisco Ortega, and his discovery . . . like so many great discoveries . . . was an accident. [3] In 1769 Don Gaspar de Portola set out from Mexico seeking the Bay of Monterey, but passed it by. He realized this fact when he sighted the outline of Punta de los Reyes (Point Reyes) and decided to send a party on to view the anchorage of Drake, Cermeno, Cabrillo and Vizcaino . . . which had been titled "Pueto de San Francisco".

That party, under Ortega, failed . . . because they found their way blocked by what is now called the Golden Gate. From a hill on the peninsula, Ortega and his party looked across miles of land-locked harbor. The date was November 2, 1769.

Further overland exploration of the Bay area followed, and in 1775 Don Juan Manuel de Ayala, captain of the ship San Carlos, [4] braved the unknown dangers of the Golden Gate and dropped anchor off what is now Sausalito at ten-thirty on the evening of August fifth . . . the first of tens of thousands of ships to find shelter in the Bay.

The discovery of this mighty harbor had been received with great excitement in Spain and Mexico City, and His Excellency Señor Frey Don Antonio Maria Bucareli y Ursua, Viceroy, Governor and Captain-General of New Spain, ordered the Captain of the Presidio of Tubac, in what is now Arizona, to make up a party and colonize the shores of the Bay. The good Captain, Don Juan Bautista de Anza, set forth with thirty married soldiers, their families and selected civilians.

In that party were men who's names have a familiar ring to San Franciscans and Californians; Alviso, Peralta, Sanchez, Castro, Benal, Valencia.

Don Jan fell ill at Monterey, and the party went on under Don Joseph Joachim Moraga. After a march of ten days, the settlers reached the shores of a lagoon that had been named for Nuestro Senora de los Dolores. Here the two priests of the party, Frs. Palou and Cambon, built a rude chapel, and in it was a celebrated first mass . . .on June 29, 1776, just a few days before the great event took place in far-away Philadelphia which was to have a profound effect upon the future of this just-born Spanish settlement on San Francisco Bay. On July 18 the San Carlos came in with supplies, and the military Presidio was established.

In October the Mission was completed, [5] and Fr. Palou wrote in his diary: "I sang Mass with the ministers, and at its conclusion a procession was formed . . . The Function was celebrated with repeated salvos of muskets, rifles and the swivel guns that were brought from the bark for this purpose, and also with rockets . . In the afternoon the men returned to the presidio and the crew went on board, the day having been a joyous one for all. The only ones who did not enjoy this happy day were the heathen". The Heathen . . who had learned about guns and white men by now . . needed the special protection of St. Francis. [6]

The Spaniards who had come as soldiers were granted vast Ranchos by the King, but agriculture was primitive and little was raised except half-wild cattle. Only the Padres planted vineyards and olive groves and fig trees. The rancheros were too busy with fandangos, cockfights and barbecues. [7] All supplies came from Mexico City, and foreign ships were forbidden to trade with California.

But by 1800 the Gulf of the Farallones was crowded with Yankee and Russian ships of the Russian-American Company, hunting sea otter and seals. Inevitably these ships and the whalers who wintered in the Bay, traded illegally with the Californians.

Charles Caldwell Drake, in his fascinating book "San Francisco A Pageant" says "The list of articles in the New England ship which visited the coast in 1813 and was seized for smuggling reads like a Sears, Roebuck catalogue."

Russian interest in the San Francisco area was intensified when Nicolai Petrovich Rezanov sailed into the Bay in 1806, seeking food for the starving Russian colony at Sitka, Alaska. He bargained with Don Jose Arguello, Commandant of the Presidio . . . and fell in love with sixteen year old Dona Conception Arguello. He got his food,but his suit for the hand of "Concha" was complicated by his Greek Orthodox religion.

Rezanov sailed for Alaska with the promise to return . . after he had crossed Siberia, persuaded the Czar to negotiate a trade agreement between Russia and California, and had visited Rome to persuade the Pope to sanction the marriage. No more was heard of Resinov, and Dora Concepcion helped the Franciscans minister to the poor and sick, there being no convents in California. Thirty-six years later she learned that her lover had died . . still true to her . . while crossing Siberia.

As the nineteenth century advanced, the little colony grew . . but not much. A few adventuresome Yankees settled in Yerba Buena (Good Herb), and trade restrictions were gradually relaxed or overlooked.

Then in 1821, the Spanish-American colonials revolted, Mexico became an independent nation . . and California was part of Mexico. Few persons realize that the Spanish flag flew over Yerba Buena and the Mission San Francisco de Asis for only forty-five years. Under Mexican domination the padres lost their power, and eventually the missions were secularized. An era was coming to an end on the West Coast of America. To the East, across the Serra and the Rockies, a ground swell was rising that would soon crash on the shores of San Francisco Bay.

[from the original Sears introduction pamphlet - 1940]

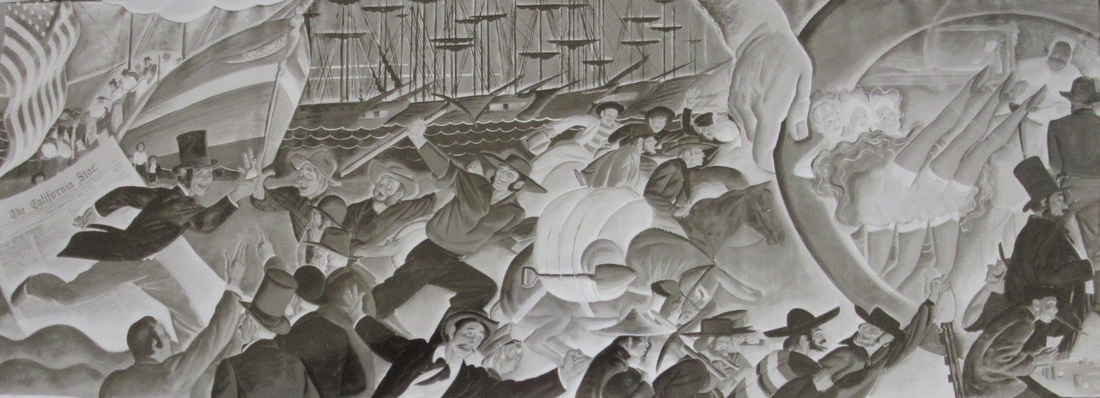

Gringos, Gold and Growth

As the nineteenth century unfolded and California left the shelter of the Spanish crown for the somewhat casual sovereignty of Mexico, a "downtown" area was added to the Presidio and Mission settlements. Known as Yerba Buena (Good Herb), because it was located in a bed of mint where the skyscrapers of the financial district now rise, this forerunner of modern San Francisco began with the building o fa store by Captain William A. Richardson, who remained behind when his British whaler sailed in 1822.

New Missions had been built near the Bay, and the two to the South . . . San Jose and Santa Clara . . . were agriculturally productive. To bring their fat cattle and the produce of the soil to the anchorage, to be traded . . . illegally . . . to the Yankee seafarers, the padres needed boats. And with the building of the necessary schooners, industry came to the Bay. It was Richardson, incidentally, who captained these Indian manned craft.

In 1834 Governor Figuroa sent word to Don Mariano Vallejo, Commandante of San Francisco, that the legislative body of Mexican California had decided to from a civil government for the "Partido de San Francisco", with an alcalde (mayor) and two "regidores". Twenty-seven men cast their votes and Francisco de Haro was named the fort alcalde.

New Missions had been built near the Bay, and the two to the South . . . San Jose and Santa Clara . . . were agriculturally productive. To bring their fat cattle and the produce of the soil to the anchorage, to be traded . . . illegally . . . to the Yankee seafarers, the padres needed boats. And with the building of the necessary schooners, industry came to the Bay. It was Richardson, incidentally, who captained these Indian manned craft.

In 1834 Governor Figuroa sent word to Don Mariano Vallejo, Commandante of San Francisco, that the legislative body of Mexican California had decided to from a civil government for the "Partido de San Francisco", with an alcalde (mayor) and two "regidores". Twenty-seven men cast their votes and Francisco de Haro was named the fort alcalde.

The Artist at work

Proudly powered by Weebly